John M. Grondelski (Ph.D., Fordham) is former associate dean of the School of Theology, Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey. He is especially interested in moral theology and the thought of John Paul II. [Note: All views expressed in his National Catholic Register contributions are exclusively the author’s.]

“Grant, we pray, that the whole creation, set free from slavery, may render your majesty service and ceaselessly proclaim your praise.”

As the liturgical year concludes, we also wrap up a year of Scriptures & Art. The purpose of this blog series was twofold: to recognize the breadth of cultural influence Catholic themes have exercised in the fine arts, and to offer readers an informal introduction to elements of art history through the lens of the Sunday Gospels. Publishing is always a challenge because authors rarely enjoy the feedback of what readers think of a project. Your thoughts in the comment section below are most welcome.

Since the 1969 Reform of the Roman Calendar, the last Sunday of the Church year is the Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. While it divides the earlier liturgical tradition of featuring Gospels of the Last Judgment on the last and first Sundays of the liturgical year, it reminds us that salvation history tends not to a what but a who — to Jesus Christ, whose triumph over sin and death is the final word of the Word-made-flesh (John 1:14) who can save us.

The Gospels for this solemnity have two themes. In Year A (2020), the Gospel (Matthew 25:31-46) presented the Last Judgment scene, where judgment is rendered according to the Beatitudes. In Year B (2021) and Year C (2022), the Gospels focus on extracts from the Passion narratives, where Jesus’ kingship is either questioned by Pilate (this year, where John 18:33b-37 substitutes for Mark) or acknowledged by the Good Thief (Luke 23:35-43). Since Jesus’ identity is defined by Mark in relation to his Passion, Death, and Resurrection, the excerpt from John fits well.

Throughout Mark’s Gospel, Jesus has invoked the “Messianic Secret” — trying to avoid too loud a premature proclamation of his identity — because he understands that his identity is comprehensible only in the context of his Passion, Death, and Resurrection. Trying to explain his identity apart from that context, particularly given the political messianic expectations of Jesus’ day, only served to encumber rather than advance Jesus’ mission. Once Jesus rises, he sends them out (Mark 16:15, 20) because now they can finally understand him.

Pilate runs into the same problem, albeit not on religious grounds. He knows the Jewish religious establishment has turned Jesus over to him out of envy (Matthew 27:18), but they kept referring to Jesus as a “king.” Pilate knew he was sitting atop a powder keg in Jerusalem — Israel had never really acquiesced in Roman rule in nearly a century since its conquest. Barabbas, the criminal in jail for whom Pilate wants to trade Jesus, was an insurrectionist. Pilate knew his job was to keep order.

So, if Jesus is a “king,” it’s worth investigating the question. Perhaps he’s just another one of these Jewish religious fanatics. Or perhaps he’s trouble. Pilate does not need political problems.

That’s the crux of today’s Gospel. Pilate thinks of “kingship” in traditional political terms. Jesus thinks of it in spiritual terms.

That’s not to say that those spiritual terms don’t threaten the political. People who take their faith seriously will always relativize Caesar’s claims. And Caesar doesn’t like that. Even if he’s elected.

Vatican II speaks of Christians as participating in the “threefold office of Christ.” Christians, by virtue of baptism, are priests, prophets, and kings. They are to offer the sacrifice of worship to God. They are to bear witness to Truth, just as Jesus says in today’s Gospel (and which today’s Caesars, like Pilate, treat with similar cynicism). And they are to be kings, who rule themselves by truth and moral rightness. They may not wield political power or influence, but they wield the moral witness of standing for the Truth even when those with power and influence ask, “what is truth?”

Although not in today’s Gospel, it’s interesting how in John the Jewish religious establishment compromises itself over the question of kingship. Israel had long resisted a king in order to emphasize that God alone was King of Israel. Yahweh’s dominion over Israel was the linchpin of Jewish identity. Yet, when Pilate asks jeeringly (but accurately) asks what he is to “do with your king,” i.e., Jesus, the chief priests voiced the ultimate apostasy contradicting more than a thousand years of Jewish identity: “We have no king but Caesar” (John 19:15).

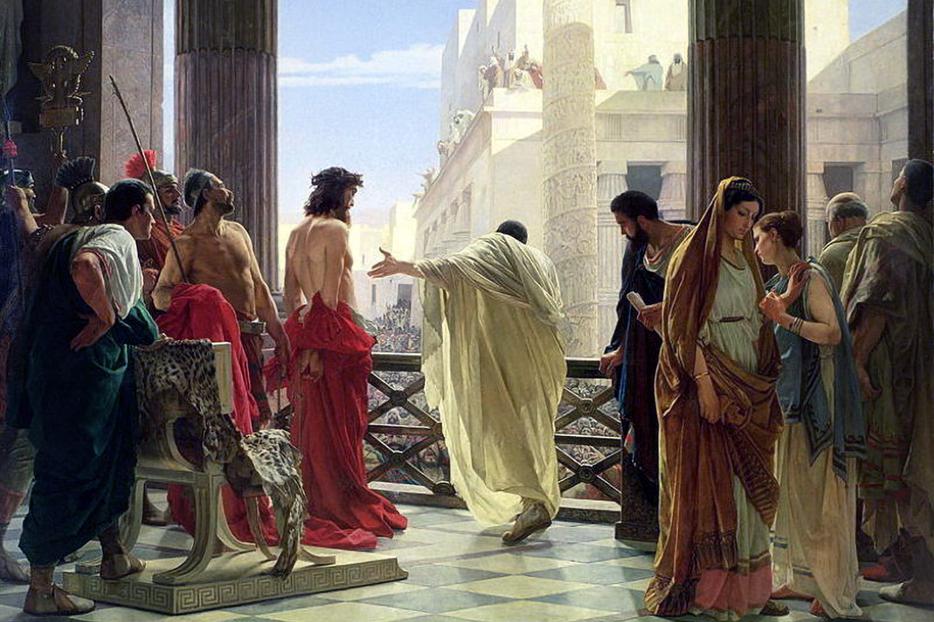

Today’s Gospel was depicted by the 19th-century Swiss-Italian painter, Antonio Ciseri. Ciseri’s 1871 “Ecce homo” (Behold, the man! — based on John 19:5) depicts Pilate’s effort to bargain with the crowd over Jesus’s fate, an effort at which he is not making much progress. Pilate points to “the man.” Jesus is bound, though we don’t see one thing we should: the marks of scourging on his back. Of critical importance to today’s Gospel, he stands there wearing the red (purple) robe (John 19: 2, 5), the color of royalty in which the soldiers dressed him to jeer him, and a “crown” of thorns on his head, another effect of the soldiers’ “king game.” This is the kind of king Jesus is: a witness to Truth, not a political player.

The viewer is an onlooker of the scene “from the inside,” i.e., inside Pilate’s court. Helmeted Roman soldiers and their local help stand beside Jesus, along with the bureaucratic administration behind Pilate’s judicial seat. Other staff, attendants, and court hang around on the left. The woman averted from the scene is probably Pilate’s wife, whom tradition names Procula. According to Matthew 27:19 — the only place she is mentioned — she is said to have sent her husband a message to avoid getting mixed up in the Jesus affair because “I suffered many things this day in a dream because of him.”

Ciseri the painter spent most of his life first in Italian Switzerland, then Florence. It’s said that his figures mirror Raphael in style and composition, but his paintings also seem to have an almost photographic quality to them (photography was coming into its own in the 19th century). His skills were early recognized in the Academy of Fine Arts. Ciseri received numerous commissions for religious art in Ticino and Italy, although Ecce homo was, according to SIKART (the Swiss Art Information website), actually commissioned by the Italian government.