John M. Grondelski (Ph.D., Fordham) is the former associate dean of the School of Theology, Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey. He is especially interested in moral theology and the thought of John Paul II. [Note: All views expressed in his National Catholic Register contributions are exclusively the author’s.]

“O blood and water, which gushed forth from the heart of Jesus as a fountain of mercy for us, we trust in you.”

Today is the Second Sunday ofEaster and Divine Mercy Sunday. It’s not a Sunday after Easter but a Sunday of Easter, because the entire Easter Season — the 50 days from Easter to Pentecost — is one unified celebration of the Paschal Mystery in which “the joy of the Resurrection” cannot be contained in a single day or even octave. Easter is 50 days long.

Last Sunday’s Gospels left us at the empty tomb — the Gospel for the Easter Vigil related the encounter of Mary Magdalene and her companions with the young man, who shows them the empty tomb. The Gospel for Mass on Easter Day recounted how Sts. Peter and John went to the tomb and found it empty, seeing the burial linens set aside and “seeing and believing.”

Today’s Gospel (John 20:19-31) relates the Apostles’ first encounter with the Risen Christ. Although a week has passed for us, the Gospel recounts the events of Easter Sunday night when the Apostles — behind locked doors, hunkered down and afraid — are visited by the Risen Jesus.

They’ve received all sorts of reports. Mary Magdalene at first sees an empty tomb, then encounters the Gardener she recognizes to be Jesus. Peter and John have also been at the vacant grave. Perhaps the disciples who went off in frustration to Emmaus have come back. In any event, the Apostles themselves now finally meet the Risen Lord.

His first post-Resurrection word to them is “Peace!” Shalom! is not just a nice, “hope-you’re-doing-well” greeting. It speaks of profound peace and reconciliation which is, after all, the whole reason Jesus came into the world. What he came for is delivered: no one need be lost except if he chooses to by indifference to the invitation.

But Jesus’ “peace” is not just a personal wish to this Twelve-some. It was his mission (“as the Father has sent me”) and is now theirs (“so I send you”). And how is that mission conveyed and to be perpetuated? Through the forgiveness of sins: “Whose sins you forgive, they are forgiven; whose sins you hold bound, they are held bound.”

The Council of Trent defined those words as the basis for the institution of the sacrament of Penance, Jesus’ Easter gift to his Church. His mission was about the reconciliation of man with God. It is clear, from his actions immediately following his first post-Resurrection encounter with his Apostles, that he does not regard that mission as accomplished, finished, checked off. He clearly demonstrates that he intends that mission to be continued through the ages, not by some “Jesus and me” form of “acknowledging Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior” but in sacramental reconciliation through his ministers in his Church. One can choose to believe or even do other things, but that wasn’t what the Jesus who went through Calvary and rose from the dead said, and it’s a queer form of “reconciliation” when the sinner decides to replace his way of forgiveness by his own.

If we understand this Easter Sunday night encounter, we see that sacramental Reconciliation is not something marginal, just “hanging out there.” It’s clear that neither the Church nor even Jesus decided to “introduce” confession as some afterthought. No — Jesus’ whole Life, Death and Resurrection was about “God and sinners reconciled” and, in announcing that peace and reconciliation to his Apostles, he makes them sharers and heralds of that mission. As I said, Jesus does not regard the mission of reconciliation as completed by him, but he clearly entrusts it to the Apostles. Nor is this mission of forgiveness disconnected from the whole skein of Jesus’ Mission: the commission to forgive sins is preceded by empowerment, specifically, “Receive the Holy Spirit.” Easter is already in some sense Pentecost: the Spirit is already in a way given, specifically for the forgiveness of sins. Jesus promised a Paraclete who would “convict the world of sin” (John 16:8) by enlightening us of the truth of ourselves before God. The gift is given. As Father David Stanley observed, this Easter night is a new creation: just as at the first creation, God sends his Spirit over the waters (Genesis 1:2) so today the God-Man sends that Spirit out again.

Today’s Gospel also gets attached to today’s celebration because it notes that, on that first Easter, St. Thomas was absent — but “a week later,” when Jesus reappears to his Apostles, he’s back. Despite what his brothers tell him, Thomas will not believe without “putting my finger in his hands and feet and in his side.” Jesus, not wanting Thomas to remain “unbelieving, but believe,” obliges. On that basis, Thomas professes his faith in the Risen Christ, which culminates in Jesus’ beatitude to you, me, and countless Christians across the generations since that encounter between Jesus and Thomas: “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.”

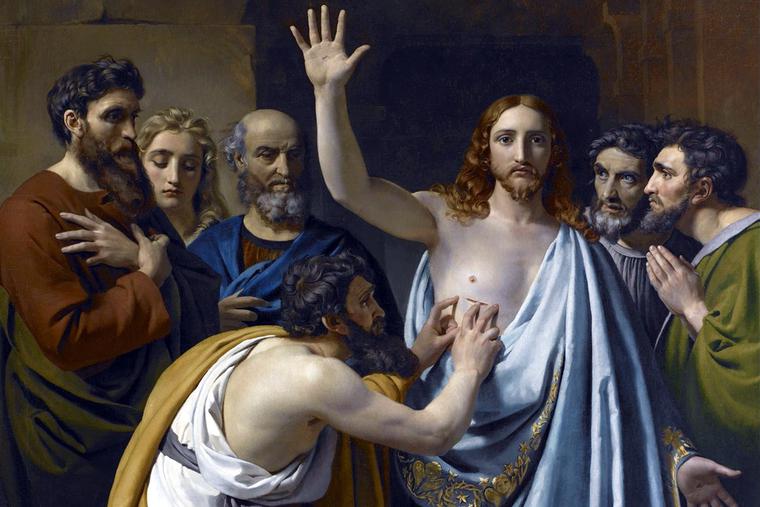

François-Joseph Navez, a Belgian painter from the first half of the 1800s, captured this moment in his 1823 oil painting, “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas.” (The painting is in Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts.)

Although it’s said that he begins incorporating some Romantic elements into his art by the time this work is painted (1823), Navez is usually classified as a neo-classical painter. Those qualities are apparent in this work. The columns leading off into the background seem classical. Jesus and St. Thomas are both clad in ways more Roman than Jewish, especially with their bare chests and shoulders. The garb is arguably necessary for Jesus (so that Thomas can probe his side), but Thomas’ clothing is clearly Roman. Jesus’ pose and facial expression is also classical: He looks more like a victorious Roman Emperor than a Jewish rabbi, quite the paradox considering that, just about 10 days earlier, the Pharisees warned Pilate that “anyone who makes himself a king becomes Caesar’s rival” (John 19:12). The other Apostles (and, presumably, Mary Magdalene?) appear attired in more typically Jewish fashion, although their positioning seems halfway between inquisitive onlookers hoping to see what Thomas finds out and an imperial retinue.

The focus is clearly on Jesus’ pierced side. Besides being the focal point of the Gospel, it’s also clearly indicated by Thomas’ hands and line-of-sight. The rightward curve of Thomas’ gold cloak also leads us to Jesus’ foot, the upward curving folds of his garment also taken us right back to his exposed side — as does his raised hand, which then also leads our eye down to his chest.

The eyes of the two disciples on the right and the first on the left are averted from that chest wound, with the two on the left looking directly at Jesus face, suggesting they already believe. Magdalene’s (?) eyes are closed, perhaps suggesting something similar. The tall Apostle on the far left does also see Jesus’ chest wound, his line-of-sight also diagonally leading us right back to it.

“From his wounded side flowed blood and water, the fountain of sacramental life in the Church,” we are told in the Preface of the Sacred Heart. Today is also Divine Mercy Sunday, and St. Faustina Kowalska reminds us that Jesus’ pierced side is also a fountain of mercy for poor sinners.

In his revelations to St. Faustina, Jesus spoke of the Feast of Divine Mercy as a special occasion for God’s absolute pardoning mercy, involving reception of the sacraments of Penance and today of the Eucharist (Diary, no. 699) — as we have seen above, both clearly Easter sacraments. In her Diary in which she recorded those revelations, Christ speaks clearly of his open side as this source of Divine Mercy: “On the cross, the fountain of My mercy was opened wide by the lance for all souls — no one have I excluded!” (no. 1182). “From all my wounds, like from streams, mercy flows for souls, but the wound in my Heart is the fountain of unfathomable mercy. From this fountain spring all graces for souls. The flames of compassion burn me. I desire greatly to pour them out upon souls. Speak to the whole world about my mercy” (no. 1190).

In conjunction with the institution of the Feast of Divine Mercy, St. Faustina also relates that Our Lord asked her that an image of his Divine Mercy be made, to be venerated on that Feast (nos. 742, 299, 327).

Eugene Kazimirowski painted that image, under the guidance of St. Faustina, in1934 in Vilnius (now Lithuania). It was first hung in a convent, then first publicly displayed in the Shrine of Ostra Brama in that city in 1935. When the Soviet Union occupied Vilnius in 1940, the picture went into hiding in Lithuania and Belarus. Today it hangs in the Shrine of Divine Mercy (Holy Trinity Church) in the Lithuanian capital. Many parishes will display it today on this Feast. The original appears below.

The painting reaffirms today’s Gospel: Jesus is our peace and reconciliation. he seeks from his wounded Heart and open chest to offer us his Mercy, which flows out just as Thomas probed it. Let us turn to that mercy in our troubled times.

Jesus, I trust in you!