SHE LEFT WITH the clothes on her back, a long blue dress and a pair of shoes she’d never wear again. It was June 8, 1991, a Saturday morning, and Shelly Pennefather was starting a new life. She posed for a group photo in front of her parents’ tidy brick home in northern Virginia, and her family scrunched in around her and smiled.

The Pennefather family in 1991, on the day Shelly entered the monastery. Shelly Pennefather is pictured in the middle. She did not pack any bags because she took a vow of poverty. Courtesy Mary Jane Pennefather

All six of her brothers and sisters were there — Little Therese, in braided pigtails; older brother Dick, tall and athletic with Kennedyesque looks. When Shelly came to her decision, she insisted on telling each of them separately.

Dick had the loosest lips in the family, so she’d told him last. Therese, 12 years old and the baby of the family, took the news particularly hard. She put on a brave face in front of Shelly, then cried all night.

They crammed a lot of memories into those last days of spring, dancing and laughing, knowing they would never do it together again. Shelly went horseback riding with Therese and took the family to fancy restaurants with cloth napkins, picking up all the tabs.ADVERTISEMENT

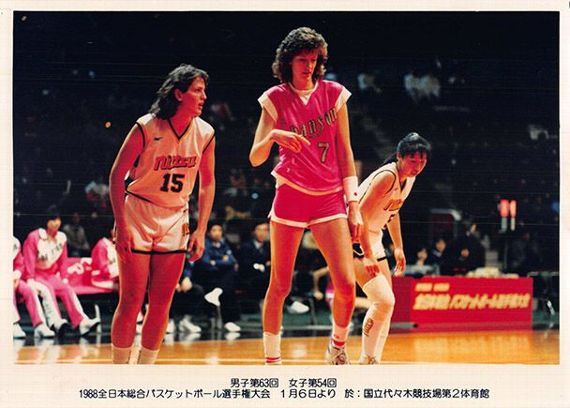

Twenty-five years old and not far removed from her All-America days at Villanova, Pennefather was in her prime. She had legions of friends and a contract offer for $200,000 to play basketball in Japan that would have made her one of the richest players in women’s basketball.

And children — she was so good with children. She had talked about having lots of them with John Heisler, a friend she’d known most of her life. Heisler nearly proposed to her twice, but something inside stopped him, and he never bought a ring.

“When she walked into the room,” Heisler said, “the whole room came alive.

“She had a cheerfulness and a confidence that everything was going to be OK. That there was nothing to fear.”

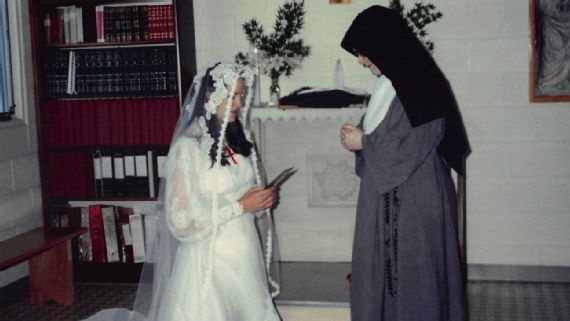

That Saturday morning in 1991, Pennefather drove her Mazda 323 to the Monastery of the Poor Clares in Alexandria, Virginia. She loved to drive. Fifteen cloistered nuns waited for her in two lines, their smiles radiant. She turned to her family. “I love you all,” she said. The door closed, and Shelly Pennefather was gone.

“The reason birds can fly and we can’t is simply because they have perfect faith, for to have faith is to have wings.” — J.M. Barrie, “The Little White Bird.”

IT’S BEEN 28 YEARS since Pennefather left home to become Sister Rose Marie of the Queen of Angels, and I’m standing outside the family’s house in Manassas, Virginia, on a warm June day, searching for answers.

I spent eight years in Catholic schools, with lessons in history from Sister Agnes Marie and kindness from Sister Rosetta. We knew that on Sundays, if you’re breathing, you’d better be at Mass. But I cannot grasp what Pennefather — now Sister Rose Marie — has chosen to do. The Poor Clares are one of the strictest religious orders in the world. They sleep on straw mattresses, in full habit, and wake up every night at 12:30 a.m. to pray, never resting more than four hours at a time. They are barefoot 23 hours of the day, except for the one hour in which they walk around the courtyard in sandals.

They are cut off from society. Sister Rose Marie will never leave the monastery, unless there’s a medical emergency. She’ll never call or email or text anyone, either. The rules seem so arbitrarily harsh. She gets two family visits per year, but converses through a see-through screen. She can write letters to her friends, but only if they write to her first. And once every 25 years, she can hug her family. That’s why we are here in early June 2019, to witness the 25-year anniversary of her solemn profession and the renewal of her vows.

The Poor Clare nuns enter this radical way of life because they believe that their prayers for humanity will help the suffering, and that their sacrifice will lead to the salvation of the world.

But why would someone with so much to offer the world lock herself away and hide her talents? Who, staring at a professional contract that would be worth the equivalent of about $400,000 today, would subject herself to such strict isolation and sacrifice? Imagine Kansas legend Danny Manning quitting basketball to become a monk.

Perhaps the best person to answer this is the woman who stood next to Shelly in that goodbye photo in front of the house, who wrapped her arm around her daughter and smiled while her heart must have wanted to stop.

Mary Jane Pennefather is the matriarch of the family, a 78-year-old who mows her own lawn and rises every morning to walk to church. When Shelly entered the monastery all those years ago, she left behind a note. Mary Jane is the strongest person Therese knows, but when she read the letter, she broke down and cried.

Mary Jane was a cheerleader once, but is steeped in a generation of Catholics who did not believe in drawing attention to themselves. She opens the door to her home and leads me to a room full of religious statues and images, which the family calls the Blessed Mother room. Her husband, Mike, died in this room. He had skin cancer, which had spread too far when doctors found it, but he went quickly, which Mary Jane considers a blessing. Sister Rose Marie couldn’t go to her father’s funeral back in 1998. She was in the monastery. But she wrote a letter that they read out loud, and her brother Dick says it was probably the most touching part of the service.

Surely, Mike Pennefather had hoped to hold his daughter again on her silver jubilee. But Mary Jane would be there. The week leading up to the Mass was stressful. How do you prepare to hug your daughter for the last time?

NUNS ARE BY no means an anomaly in today’s society. The 2018 Official Catholic Directory lists 45,100 sisters in the United States. But cloistered nuns, with all of their combined orders, account for only a fraction of that number. The Poor Clare Colettines, according to the directory, have about 160 sisters in this country.

There were hints, all along, that Pennefather was different. In sixth grade, a teacher asked the class an ordinary question: What do you want to be when you grow up? The teacher wasn’t prepared for Shelly’s answer. “I’m going to be a saint,” she said. The whole class laughed, assuming she was joking. Pennefather liked to regale her friends with jokes and magic tricks.

Her childhood might have inadvertently prepared her for life as a cloistered nun. Mike Pennefather was an Air Force colonel, taking the family to Germany and Hawaii and New York, so she’d already seen a lot of the world by her 20s. Her mom was — and is — about as anti-technology as a person can be in 2019. Mary Jane doesn’t own a cell phone, she could go on for hours about how cell phones are destroying the human experience, and a few decades ago, she was saying pretty much the same thing about television.

Children of the ’70s often have stories of their forays into alcohol or drugs; the Pennefathers’ illicit pursuits centered mostly on the forbidden television. They’d wait until Mary Jane was gone, pull it out of the closet, rig up a coat hanger for an antenna, and stand in just the right spot to get reception.

“I think my sister watched ‘Fantasy Island’ and got caught and got in trouble,” Therese said. “You had to invent your own entertainment, and we did all kinds of stupid stuff. “I absolutely wouldn’t trade any of it.”

The Air Force gave the Pennefathers new playgrounds every few years, and assured that they would almost always be safe. Want to play kick the can at 11 o’clock at night? No problem. Leave the base lights on and go ahead and invite 20 other Air Force brats.

Mary Jane might have seemed strict, but Mike was actually more intimidating. He was a bear of a man with a loud voice and a physics degree. Mike Pennefather did not tolerate foolishness. He taught all seven of his children how to shoot a basketball, and when he had finished with that, he taught other people’s children how to do it, too.

The Pennefathers had six children in eight years, and Shelly was born between two brothers, two basketball playmates. The elbows and charges she took made her unstoppable when she finally played against girls. At nighttime, Mary Jane would gather the whole family together to pray the rosary. It didn’t matter if it was midnight; she waited until everyone was home.

The rosary is considered one of the most powerful symbols in Catholicism. Each of the 59 beads represents a prayer. The Hail Mary is said 53 times during the rosary. The repetition is intended to bring spiritual contemplation and peace. At the Pennefather house, after the last prayer was said, each child gave Mary Jane and Mike a kiss goodnight.

COACH HARRY PERRETTA also prayed the rosary every day, a practice that came in handy in his pursuit to lure Pennefather to Villanova. If Pennefather played today, her recruitment might have been as big as that of Breanna Stewart or Elena Delle Donne.

Pennefather went 70-0 in her first three years of high school at Bishop Machebeuf in Denver and won three state championships. When her dad was transferred to upstate New York her senior season, nothing changed. Utica’s Notre Dame High went undefeated, too.

Pennefather had no interest in the recruiting process. She hated the attention that it brought, and didn’t like talking on the phone. So it was hard for any coach to get a read on her. Perretta talked to her about his devotion to the Blessed Mother Mary, and they connected. She committed to Villanova, the oldest Catholic university in Pennsylvania. Their bond was tested early. Her freshman year, they clashed constantly. “She was a very lazy basketball player at first,” Perretta said. “She didn’t work hard on the court when she came here.” He said it wasn’t necessarily her fault; she was so good in high school that she probably didn’t know what playing hard meant. But he had to get through to her. He yelled at her and kicked her out of the gym, and nothing seemed to work. In her sophomore season, Pennefather considered transferring.

She’d leave campus on weekends, seeking solace at teammate Lisa Gedaka’s house in New Jersey. Gedaka, a freshman, would go back a lot because she was homesick. “I always remember hearing about how she was searching,” Gedaka said. “Was this the right place to go? What is the meaning? Why is she here? And I remember saying to her once, ‘Shelly, did you ever think that maybe this is God’s will that you should be with us here at Villanova? This is where you’re meant to be.'” Somehow, some way, Pennefather and Perretta finally clicked. “God gave you this gift,” Perretta told her. “You’re not really using it to the fullest extent.”

From there, she didn’t hold anything back. There was one game, junior year, when she was so overcome with menstrual cramps that they were almost debilitating. As the team left for the gym, Perretta told her to just stay at the hotel. A couple of minutes before tipoff, Pennefather emerged from the locker room, in agony, with her sneakers still untied. “I’m going to try to play,” she told him. She mustered enough strength to tie her shoes when the horn sounded. There was no time for any warm-up. She made all nine of her shots in the first half.

The Wildcats’ teams in the mid-to-late 1980s were lucky. They were a collection of people who knew, when they were freshmen, that they’d stay friends forever. They demanded the best of each other. It was a different time, before NCAA-regulated practice schedules and transfer portals. “We could say stuff to each other,” said former Wildcats point guard Lynn Tighe. “If somebody was being a pain in the butt, I had no trouble telling them, and if I was a pain in the butt, I was told about it. We were open to each other, and nonsense didn’t fester.”

Pennefather was roommates with Tighe, and you can imagine her glee when she found out her point guard had a small television. Pennefather had one movie she would watch constantly on the VCR. “The Sound of Music.” She subjected everyone to it, belting out Julie Andrews songs on the team bus. “I wouldn’t say she had a good voice,” Tighe said. “But it wasn’t bad. She knew every word to every one of them.”

But Pennefather did have the most beautiful shooting touch in all of women’s basketball. She scored 2,408 points, breaking Villanova’s all-time record for women and men. She did it without the benefit of the 3-point shot, and the record still stands today.

In 1987, she won the Wade Trophy, given to the best women’s college basketball player. She eventually threw away all of her trophies — “I don’t think she cared about them at all,” said her sister, Therese — but spared one, the Wade Trophy. She gave it to Perretta.

The WNBA did not exist when Pennefather graduated from Villanova, but women’s professional basketball overseas offered good money. She signed with the Nippon Express in Japan, the place where her whole life would change.

The pace in Japan was much slower — the Express played just 14 games in the span of four months — and it jolted Pennefather. Away from her college teammates and the daily chaos of her large family, she felt homesick and alone in a faraway city. Her team started 0-5. If they finished at the bottom of the division, she would need to stay in Japan for another two months to play a series of round-robin games.

She desperately wanted to go home, and vowed that if her team could finish in the top six, allowing her to go home rather than stay those two months, she would spend that time doing volunteer work.

The Express turned their season around and finished third. Pennefather returned to the U.S. and fulfilled her promise by working in a soup kitchen at the Missionary Sisters of Charity in Norristown, Pennsylvania. In a convent full of tiny nuns, the 6-foot-1 basketball player stood out. She felt even more out of place that next season in Japan. She did everything she could to keep busy, reading books, learning Japanese, teaching English. But Pennefather still felt a deep emptiness. “She was forced to go into solitude,” said John Heisler, her childhood friend. “There was nobody else, just her and God.”

HEISLER WAS SORT of a mystery man for many years. Pennefather’s teammates used to say that they thought she’d do one of two things in her life — marry this guy she spent summers with or become a nun. But not a cloistered nun, of course.

Sports Illustrated did a story on Pennefather’s rare sacrifice in the late 1990s, but Heisler’s name wasn’t mentioned. He was nowhere near being ready to talk about her back then. But now Heisler is really helpful. He wants people to understand, even if he still doesn’t completely get it himself. “It’s a mystery to me too about why they’d take somebody so talented, so giving, so energetic,” he said. “She could help so many other young ladies to be women … to be strong, too, in their identity. Why should she be so hidden now? I’ve been really thinking … about the mystery of the stars. They’re so distant, yet they’re so beautiful.”

They met in grade school on a base in Wiesbaden, Germany. He’d never met a girl like her — confident yet self-effacing; strong but kind enough to defend anyone who was being picked on. Heisler came from a large Catholic family, too. At one point, the families prayed the rosary together. They eventually were shipped to different places, but they always seemed to find each other. Heisler had three passions growing up: sports, comic books and stories about saints. He was fascinated by St. Francis of Assisi, who eventually helped St. Clare start an order called the Poor Clares.

When he was older, Heisler developed another interest: Shelly Pennefather. Heisler went on to the Air Force Academy, and one morning he woke up content with his life and the fact that he flew F15s but also plagued by one question: What if God has another plan for me? In a move that was both bold and not very well thought out, he withdrew from his classes at the academy, went back to his family’s home in Maine, then drove to Villanova to see Pennefather. They’d spend their summers together white-water rafting and talking about anything.

Despite their affection for each other, they were never intimate. John Heisler, you see, was battling his own inner voice, the one that told him he should become a priest. If a calling came from a booming voice above the clouds, like in the movies, it would be easy. Heisler’s was a gnawing pain. He went back to school to become an electrical engineer, and pursued Pennefather through different stops in their lives, but that pain just wouldn’t go away. It was like a kill switch that told them they’d never be together.

In early 1991, during her third season in Japan, she called Heisler and asked him to meet her in Virginia so they could talk. “What’s going on?” he asked. “Well, I’m entering the Poor Clares,” she told him, “and this is our last time … to spend time together.” Heisler’s heart dropped. But in a way, it was freeing. Father John Heisler had nothing holding him back. Eight years later, he was ordained.

WHEN PENNEFATHER GOT back from Japan in 1991, she wanted to tell her closest friends about her decision in person. She traveled to New Jersey to tell Lisa Gedaka and to Pennsylvania to tell Lynn Tighe. Tighe owned a deli back then, and she and Pennefather were peeling potatoes when her former teammate dropped the news. Pennefather never stopped peeling.

“Lynn, I would never choose this for myself,” Pennefather told her. “I would never leave my family and my friends. But this is what I’m called to do. I know it. God is calling me. And I’m going to do it.” But Tighe, Karen Daly and Kathy Miller, all part of the same Villanova class that met each other as freshmen in 1983, wanted more answers. They insisted on going to the monastery and talking to the mother superior. They wanted to know everything they could about the life of a cloistered nun. They wanted to make sure their teammate would be OK.

Pennefather gave her friends a couple of questions to ask, too, a true sign she had little idea what she was getting herself into. Miller said that they struck a deal with the mother superior that day: That in 2019, the three of them would be able to hug Pennefather during her silver jubilee. Just like family.

SEASONS PASSED FOR everyone but Sister Rose Marie. Tighe became an associate athletic director at Villanova; Lisa Gedaka got married, had children and became a high school basketball coach. Her oldest daughter plays basketball, too, and now Mary Gedaka is a forward at Villanova, playing under an older and somewhat mellower Harry Perretta.

Perretta also brokered a backdoor deal with the Poor Clares. He’d bring the sisters some much-needed supplies every summer in return for his own yearly visit with Sister Rose Marie.

So every June, he drives three hours down I-95 to the monastery, delivering necessities such as ginger ale and Reese’s peanut butter cups. Sometimes, he’ll bring along one or two of her old teammates to (wink, wink) help. They can see her through the screen and hold their hands up to hers.

One time, Perretta was visiting Sister Rose Marie when his phone rang. “What’s that?” she asked. She’d never seen a cell phone.

If Perretta or any of Sister Rose Marie’s teammates are struggling, they can call the monastery and ask the mother superior to pass along prayer requests. They pray for humanity and the things they can’t see. They prayed for the victims of 9/11 even though they never saw any pictures of the towers falling or knew the names of the people who died. “I didn’t understand it at first,” Perretta said. “But if you believe in the power of prayers, then they’re doing more for humanity than anybody.”

IT RAINED ON June 9, the day of Sister Rose Marie’s jubilee Mass. The bishop of Arlington, Virginia, came, and people in Sunday suits and dresses scurried to find seats in the monastery’s tiny chapel. Perretta’s two sons, strapping young men, stood in the back and craned their necks to see the altar. They weren’t even born when Pennefather left.

Shortly after the homily, two wooden doors opened and the whole chapel let out a silent gasp. There she was, 53 years old, standing before them, with no screen. Without even scanning the crowd, she immediately fixed her eyes on the pew where her mother sat. Her face lit up.

Sister Rose Marie renewed her vows. Then a procession line formed in front of her. Mary Jane was first. Sister Rose Marie held her hands out as her mother drew closer. The Pennefathers have never been a touchy-feely family, but when mother and daughter embraced, it seemed to last an eternity. Neither one wanted to let go. “I’ll be here at 103 if you can hang in there,” Mary Jane told her daughter. “I’ll try,” Sister Rose Marie said.

She hugged nieces and nephews she had never touched before. She embraced siblings whose hair had turned from dark to gray. Perretta got his hug. Tighe, Daly and Martin weren’t sure whether anyone would remember that deal they made with the mother superior so many years ago. But they slipped into the back and hugged her, too.

And in that receiving line stood Father John Heisler. He saw the woman he had known and loved for most of his life, and they gave each other a knowing smile and an embrace. “We made the right decision,” she told him. “No regrets,” he said.

MOST OF HER teammates knew, going in, that they weren’t going to get a hug because it was supposed to be for family only. But they didn’t want to miss this moment. They traveled from Washington State and points up and down the Eastern seaboard.

One ex-Syracuse player who met Shelly at a camp more than three decades ago drove three hours to see her, too. She means that much to people, Marita Finley said. A few hours after the Mass, Sister Rose Marie’s teammates were allowed a visit. It was the first time they’d been together in decades. They didn’t know what to expect. When she appeared behind a screen, the whole room erupted in cheers.

“I just want to say one thing,” Pennefather told them. “I’ve heard every comment you said about me at alumni gatherings in the past. These will have eternal repercussions.” Everyone laughed.

A woman who spends 23 hours a day in silence seamlessly launched right into conversation. There were no awkward gaps. It was as if they picked back up after seeing each other at the last team reunion. “I mean, it doesn’t really surprise me that some of us should have ended up incarcerated,” she deadpanned. “The surprise was that it was me.”

The years had been kind to Sister Rose Marie. She lifts weights three times a week and stretches on the other days, except, of course, on Sundays. No, she does not play basketball, but every so often, the sisters will engage in a game of stickball. With her old teammates around her, clinging to each other’s words, they caught up on families and careers, then, without being asked, Sister Rose Marie shared a story. Her story.

She was in Japan that first year and wanted to go home. “So I made this deal with God,” she said. She told them that the missionary work moved her so much that she went back every summer after that. One year, she was invited to a retreat, where she was asked to read a Bible verse, John 6:56: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in him.”

And that, she said, is when it hit her. She felt that God was right there, 20 feet in front of her. She kept reading, and when she closed the Bible, she said a silent prayer. She was stunned. She walked into church the next day, genuflected at the tabernacle like she always did, and realized that she was no longer alone.

“You can look back now and you see how providentially our Lord just kind of took me and put me there in that place where I could just develop, you know?” she told them. “And then I just kind of felt that he was asking me to serve this sort of radical kind of call, which is the hardest thing I ever did. But I’m grateful I did, and here I am. Incarcerated.”

But she never really left them. Her letters got them through marriage problems and deaths and child-raising crises. Some of the women brought their children to the monastery, just to see her.

“I love this life,” she told them. “I wish you all could just live it for a little while just to see. It’s so peaceful. I just feel like I’m not underliving life. I’m living it to the full.”

THE PENNEFATHERS THREW a jubilee reception at a Knights of Columbus hall. They could have catered it, but Mary Jane wouldn’t have it. She spent weeks making everything, the lasagna and chocolate cake and orange slush. Maybe if she kept moving, she wouldn’t have to think about the finality of the hug. If anyone is going to make it to 103, her children say, it’s Mary Jane. She’s lost a husband and two grandchildren, but she is constant, like the spring cherry blossoms up the highway.

Sister Rose Marie’s sacrifice was Mary Jane’s sacrifice. She no doubt was filled with pride and sorrow when Shelly made her decision. She keeps a box at the house that contains her daughter’s hair. It was cut after she went into the monastery. Mary Jane isn’t sentimental about it; she doesn’t open the box to feel closer to her daughter. But she’s kept it, and Shelly’s letter, after all these years.

Mary Jane does not want to share the letter. It’s too personal. But she will recite one line, from memory. “I realize that I won’t hear the laughter of my brothers and sisters anymore.”

Shelly’s younger sister, Jean, also became a nun. She’s not cloistered and can hug her family, use a cell phone and drive.

Mary Jane does not want people to think that someone who chooses either of these lives is an oddball. But she knows that no matter what she says, people will not understand.

She got out of her seat in what they call the Blessed Mother room and searched through some drawers and pulled out a photo album. She stopped at an old picture of a young girl wearing a veil. “That’s me,” Mary Jane whispered. “I entered, too.” She was 14 years old in the picture. The convent was vast, and 2 ½ hours away from her home in Louisiana. Nine months in, it dawned on her. I shouldn’t be here. She went home, finished high school, went to college, met Mike and never looked back.

She, too, has no regrets. “Well,” she said, “look at the fruits of my life.”